NICE Rapid Blog

Latest news and knowledge to share.

Vacuum Casting Applications in the Toy Industry: From Prototyping to Production

The journey from a toy designer's sketch to a child's hands is paved with critical manufacturing decisions. Among the various production methods available, vacuum casting occupies a unique and invaluable position in the toy industry. This manufacturing process, also...

Applications of Blow Molding in Manufacturing Medical Bottles

Blow molding is a highly versatile and efficient plastic manufacturing process that plays a crucial role in producing a wide array of medical products, especially medical bottles. These bottles are integral components in healthcare settings, used for storing and...

How Plastic Injection Molding Enhances Manufacturing Processes and Quality

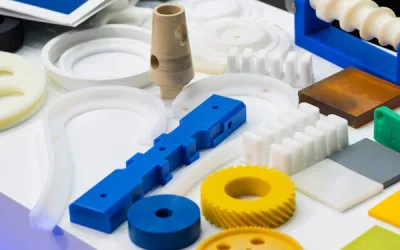

Plastic injection molding has become one of the most crucial and widely used manufacturing processes in the modern industrial landscape. Its ability to produce complex, high-quality components efficiently and on a large scale has revolutionized industries such as...

The Critical Role of Silicone Rubber in Hair Dryer Electrical Safety

Hair dryers are among the most commonly used household appliances worldwide. They offer convenience and efficiency in styling hair, but their safety depends heavily on the materials used in their construction. One such crucial material is silicone rubber, which plays...

How SLA Manufacturing Transformed Hearing Aids: A Revolution in Precision, Comfort, and Accessibility

The hearing aid industry has undergone a remarkable transformation over the past few decades, driven by technological advances that enhance device performance, personalization and accessibility. Among these innovations, Stereolithography (SLA) manufacturing has...

Blow Molding: A Preferred Manufacturing Process for Hollow Plastics

In the vast and competitive landscape of industrial manufacturing, choosing the optimal production methodology is a critical strategic decision. For the creation of hollow plastic components - a category that spans from microscopic medical vials to massive industrial...

Top Reasons Why Injection Molding Is a Popular Manufacturing Method

In the vast landscape of manufacturing, few processes have achieved the ubiquity and enduring relevance of plastic injection molding. From tiny gears in wristwatches and the intricate housing of smartphones to robust components under car hoods and one-off items in...

Liquid Silicone Rubber (LSR) Molding for Baby Bottle Nipples

Of all the applications for Liquid Silicone Rubber (LSR) molding, few are as critically important or technologically demanding as the manufacture of baby bottle nipples. This component is more than just a piece of consumer plastic; It is a safety-critical,...

3D Printing Flower Pots: A Guide to Customized Horticulture

In recent years, 3D printing technology has revolutionized numerous industries, from manufacturing to healthcare, and now it is making a major impact in horticulture. One of the most innovative applications is the creation of customized flower pots, which allows...

Vacuum Casting Applications in Automotive Sensors

Vacuum casting plays a crucial role in the prototyping, validation, and low-volume production of automotive sensors, where precision, durability, and rapid iteration are essential before committing to high-cost mass-production tooling. Key Automotive Sensor...

Revolutionizing Sound: How 3D Printing is Creating the Future of Speakers

In recent years, technological advances have continually reshaped the way we experience sound. Among these innovations, 3D printing stands out as a transformative force, offering unprecedented possibilities in speaker design, customization and manufacturing. This...

Pressure Die Casting in Vacuum Cleaner Casing Design and Manufacturing

The modern vacuum cleaner is a symphony of engineering, balancing powerful suction, efficient filtration, user ergonomics and durable construction. Central to the robustness and performance of this appliance is a crucial manufacturing process: pressure die casting....

Prototype and Manufacturing Services Near By

Rapid Prototyping Services

Turn your ideas into reality fast with our rapid prototyping services. From concept to 3D printing, we bring your vision to life quickly and accurately. Stay ahead of the curve and accelerate your product development process with us.

Silicone Molding

Experience seamless production with our silicone molding expertise. Our precise techniques ensure high-quality, custom molds that bring your designs to life with exceptional detail and durability. Whether you’re crafting prototypes or mass-producing products, our silicone molding services offer efficiency and reliability, empowering you to achieve your goals with confidence.