Selecting the Right Rapid Prototyping Method: A Technical Guide to Additive Manufacturing Technologies

Rapid prototyping plays a critical role in accelerating the product development cycle, enabling engineers and designers to rapidly produce functional models, evaluate design concepts, and identify potential issues early in the process. Choosing an appropriate fabrication method for prototyping is essential, as each technique offers distinct advantages and limitations depending on the required accuracy, material properties, complexity, and cost constraints. Below, we provide a comprehensive analysis of the most prominent rapid prototyping technologies, elucidating their underlying principles, material compatibilities, process intricacies, and ideal application scenarios.

Stereolithography (SLA): High-Resolution Photopolymerization

Principle & Process:

Stereolithography, often abbreviated as SLA, is one of the earliest and most mature additive manufacturing technologies. It employs a highly focused ultraviolet (UV) laser to selectively solidify a liquid photopolymer resin contained within a vat. The process begins with the resin surface being spread into a thin, uniform layer via a recoating mechanism. The laser then traces a cross-sectional pattern of the part onto the resin surface, inducing photopolymerization at specific points. This curing process causes the resin to transition from liquid to solid, adhering to the previously cured layer. After each layer is completed, the build platform lowers incrementally, and the process repeats until the entire part is formed.

Material Characteristics & Limitations:

SLA resins are chemically formulated to offer excellent detail resolution and smooth surface finishes. However, the cured parts tend to be relatively brittle and exhibit limited mechanical robustness compared to other processes. Their susceptibility to environmental factors such as humidity, UV light exposure, and chemical degradation can impact long-term durability. Additionally, post-curing steps—such as UV exposure and thermal curing—are often necessary to enhance mechanical properties and stability.

Application & Suitability:

Ideal for producing highly detailed prototypes, concept models, dental and jewelry applications, and intricate geometries where surface finish quality takes precedence over strength. Cost-effectiveness makes SLA suitable for small batch production of prototypes that require fine detail.

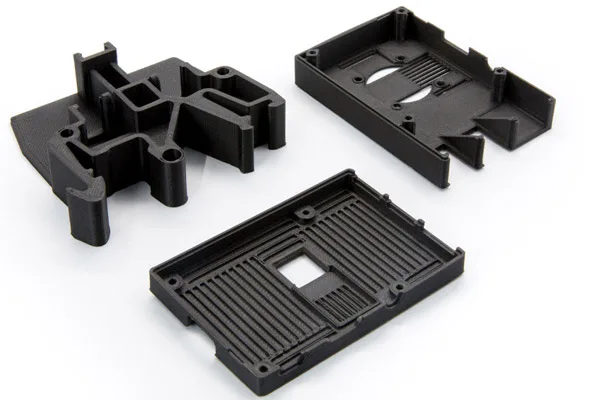

SLS parts

Selective Laser Sintering (SLS): Durable Functional Prototypes

Principle & Process:

SLS employs a high-powered CO₂ laser to selectively sinter powdered thermoplastic materials, predominantly nylon-based polymers like polyamide, or elastomeric variants such as thermoplastic polyurethane (TPU). The process involves spreading a thin layer of powder across the construction platform, followed by a laser scan that selectively fuses the powder particles according to a digital design. Once a layer is completed, a new layer of powder is spread, and the process continues iteratively. After the construction is complete, the unsintered powder remains in contact with the part, providing support during fabrication.

Material & Mechanical Properties:

SLS components exhibit superior mechanical properties, including high tensile strength, shock resistance and flexibility, making them suitable for functional testing and end-use applications. This process produces complex geometries without the need for support structures, as the excess powder acts as a natural support system. However, the surface finish is typically rougher than SLA or PolyJet and often requires post-processing for cosmetic refinement.

Application & Suitability:

Well-suited for the production of durable prototypes, functional test fixtures, and low-volume end-use components where mechanical performance is critical. This is particularly advantageous for complex, lightweight geometries and internal features that are difficult to achieve with subtractive fabrication.

Direct Metal Laser Sintering (DMLS): High-Strength Metal Prototypes

Principle & Process:

DMLS, also referred to as Laser Powder Bed Fusion (LPBF) in some contexts, is an additive manufacturing process optimized for metal components. It utilizes a high-energy fiber laser to selectively melt and fuse metal powder particles—such as stainless steel, titanium alloys, aluminum, or cobalt-chromium—layer by layer. The process begins with a thin layer of metal powder spread across the build platform. The laser then scans the cross-section of the part, melting the powder to create a dense, metallurgically bonded structure. After each layer, the build platform lowers, and a new powder layer is deposited, repeating until the part is complete.

Material & Mechanical Attributes:

DMLS parts possess near-full density and mechanical properties comparable to traditionally manufactured metal components. They can withstand high stress, thermal cycles, and corrosive environments, making them suitable for aerospace, biomedical, and automotive applications. Post-processing steps such as heat treatment, surface finishing, and hot isostatic pressing are often employed to optimize properties.

Application & Suitability:

Primarily used for producing complex, functional metal prototypes, tooling, and end-use parts. Due to high costs and slower build times, DMLS is generally reserved for small batch production, design validation, or custom components requiring high strength and durability.

FDM

Fused Deposition Modeling (FDM): Cost-Effective Layer Extrusion

Principle & Process:

FDM operates through the extrusion of thermoplastic filaments heated to their melting point. The filament, typically ABS, polycarbonate (PC), or composite blends, is fed through a heated nozzle that deposits material onto a build platform in a controlled manner. Layers are built up sequentially, with each layer fusing to the previous one upon cooling. The process is governed by G-code instructions derived from CAD models, enabling precise control over deposition paths and layer thicknesses.

Material & Mechanical Properties:

FDM parts are generally strong and durable, suitable for functional prototypes, jigs, and fixtures. However, surface finish quality and dimensional accuracy are typically lower compared to resin-based processes. Warping and layer adhesion issues can occur, especially with larger parts or high-temperature materials.

Application & Suitability:

Best suited for producing robust, functional prototypes, especially where cost and speed are critical considerations. Ideal for engineering validation, concept visualization, and testing in real-world conditions.

Multi-Jet Fusion (MJF): Rapid, Colorful, and Functional Prototypes

Principle & Process:

MJF employs a proprietary inkjet array to selectively deposit the fusing agent onto a bed of nylon powder. Infrared light then passes over the powder bed, fusing the area where the fusing agent is applied. The residual powder acts as a support medium, and after construction, excess powder is removed and the part undergoes post-processing steps such as dyeing for aesthetic enhancement.

Material & Properties:

Parts produced via MJF offer high-speed build times, good mechanical properties, and the ability to produce full-color or textured prototypes. The process is capable of producing complex geometries with relatively fine detail, although it may not match the ultra-high precision of SLA or PolyJet for small features.

Application & Suitability:

Optimal for rapid production of functional prototypes, aesthetic models, and low-volume manufacturing where speed and multi-material/color options are advantageous.

Polyjet overmolded parts

PolyJet Technology: Multi-Material, Multi-Color, High-Resolution Printing

Principle & Process:

PolyJet employs inkjet print heads to deposit tiny droplets of photopolymer resin onto a build surface, which are immediately cured with ultraviolet light. This process allows for the layering of multiple materials and colors within a single build, producing highly detailed and complex geometries with smooth surface finishes.

Material & Mechanical Traits:

PolyJet parts can emulate the look and feel of various plastics and elastomers, making them ideal for visual prototypes and ergonomic models. However, their mechanical strength and chemical resistance are generally limited compared to SLA or SLS counterparts.

Application & Suitability:

Best for visual and aesthetic prototypes, multi-material assemblies, and complex geometries requiring high detail and color fidelity. Less suitable for functional testing involving high stresses or environmental exposure.

Computer Numerical Control (CNC) Machining: Subtractive Precision and Strength

Principle & Process:

CNC machining involves the removal of material from a solid block of plastic or metal using computer-controlled cutting tools such as mills, lathes, or routers. The process is driven directly by CAD models, translating digital instructions into precise, subtractive manufacturing operations.

Material & Mechanical Properties:

CNC-produced parts are typically of high strength, excellent dimensional accuracy, and surface finish. They can be produced in a broad range of materials, including metals, composites, and engineering plastics, with complex geometries achievable through multi-axis machining.

Application & Suitability:

Ideal for functional prototypes, tooling, and production-ready samples where mechanical integrity and precision are paramount. However, CNC machining can generate significant material wastage and may involve longer lead times and higher costs compared to additive methods.

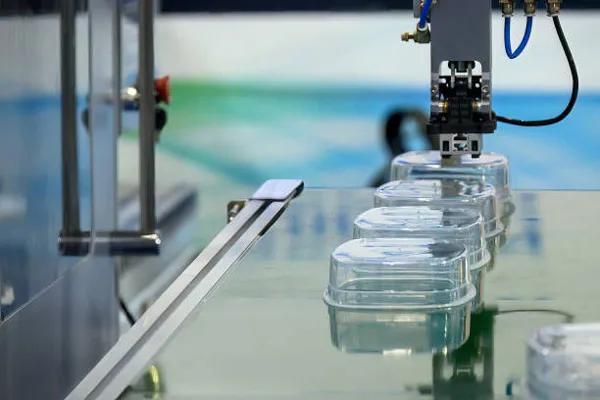

Plastic components

Injection Molding: High Volume Production of Prototypes and Small Batches

Principle & Process:

Injection molding involves heating thermoplastic resins until molten and injecting them into a precision engineered mold cavity under high pressure. Once cooled, the mold opens and the solidified part is ejected. Molds are typically fabricated from steel or aluminum and can produce thousands of identical parts, depending on the mold material and design.

Material & Properties:

This procedure affords excellent surface finish, high dimensional accuracy, and robust mechanical properties. It supports a wide range of thermoplastics and thermosets, enabling the production of prototypes that closely resemble the final production parts.

Application & Suitability:

Primarily used once a design has matured and a high volume of identical parts is required. Initial tooling costs can be substantial, making it less practical for early prototyping. Often, initial prototypes are produced via additive manufacturing or CNC machining before transitioning to injection molding for mass production.

Conclusion

Selecting an appropriate rapid prototyping technique relies on a nuanced understanding of design requirements, material properties, desired surface quality, mechanical properties, production speed, and budget constraints. Advanced additive manufacturing techniques such as SLA, SLS, DMLS, MJF and PolyJet offer a diverse range of capabilities, from highly detailed visual models to functional, load-bearing prototypes. Meanwhile, traditional methods such as CNC machining and injection molding serve as essential tools to achieve high precision and volume production once the design is finalized.

By thoroughly evaluating the technical properties of each process and aligning them with project objectives, engineers and product developers can optimize their prototyping workflow, reduce time-to-market, and ultimately deliver innovative, high-quality products that meet or exceed consumer expectations.